This is article 1 in a series about Kubernetes cost optimization. I explore how cost waste hides across compute, storage, and networking. More importantly, I will explore how to tackle it with automation instead of manual audits.

A team right-sizes their deployments very well, and cuts compute costs by 30%. Then someone looks at the rest of the bill and starts investigating. Dozens of volumes and disks sitting unattached. Load balancers fronting services with 2 requests per hour. An entire development environment running 24/7 with no activity for the last 3 days. The compute cuts they celebrated? A fraction of the total waste.

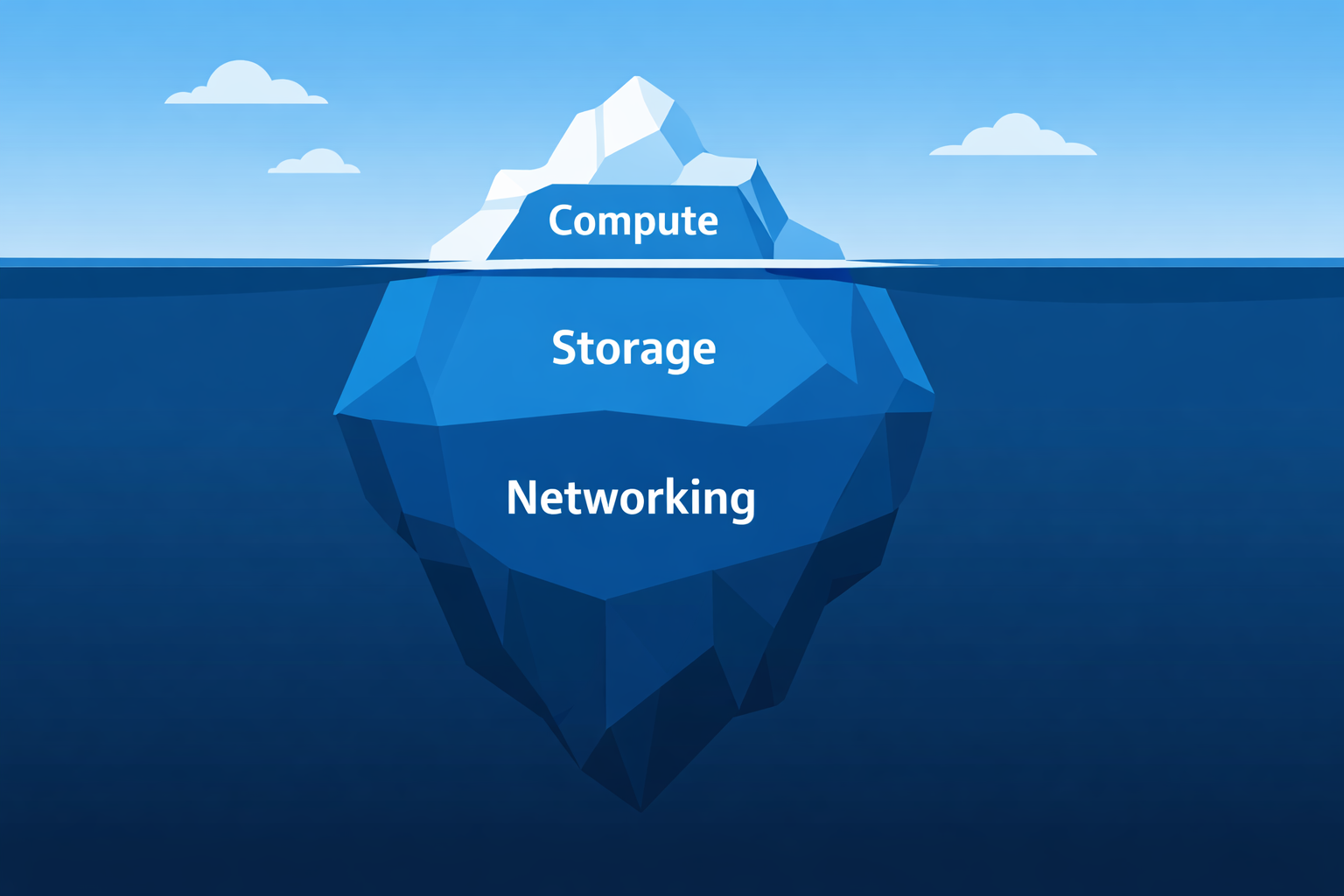

This pattern keeps appearing in many kubernetes environments. Teams treat cost optimization as a compute problem: tune your requests and limits, maybe set up an auto scaler. But compute is only one of three layers where kubernetes quietly burn money. Storage and Networking are the other two, and they are often overlooked.

The Compute Layer: Where Everyone Starts (and many Stop)

Compute resources are the obvious and natural target. CPU and memory requests concern every pod you deploy, and the gap between what is requested and what is actually in use is usually massive. Studies and tooling vendors report that workloads run at 20-40% average utilization of actual resources. That means that more than half of the compute resources you’re paying for is doing nothing.

Most teams know this. The problem is not awareness, but action. Right-sizing a workload requires looking at actual usage data, making changes, and accepting the risk that your workload might get throttled, or even OOMKilled. As a result, the requests field stays inflated “just in case”, and nobody revisits them until the cloud bill triggers an internal crisis.

The more interesting waste on the compute side is “environments that shouldn’t be running at all”. Development and staging environments running identical replicas to production, all night and all weekend.

I’ve used KEDA to scale non-production workloads to zero based on cron schedules in some cases. In other cases I set up KEDA to scale workload to zero based on activity. So the environments are scaled to zero by default and only “wake up” when there is an incoming request.

In those cases, the savings were immediate and significant. If your dev environment runs 24/7 but your developers work 8-hour days on weekdays, and not on all applications at the same time, you’re paying for roughly 70% of compute you’ll never use.

Autoscaling helps, but it’s not enough. You also need something enforcing sane defaults. If a developer can deploy a workload requesting 4 CPU cores without any guardrail catching it, your autoscaler is just efficiently scaling up waste.

The Storage Layer: The Silent Budget Leak

Storage is where cost waste goes to hide. You often don’t see it, and nobody notices storage waste because it does not create an incident. It doesn’t crash. It doesn’t page anyone. It just grows, slowly, silently and expensively. There are many scenarios that can lead to this.

The #1 cause by far is the PersistentVolume Reclaim Policy in a StorageClass (reclaimPolicy) or a PersistentVolume (persistentVolumeReclaimPolicy). Having this set to Retain will keep any disk you’ve created for that PVC after you delete it.

Other situations may lead to orphaned Disk on your cloud account:

- StatefulSets deletion without cleaning up PVCs

- Removing finalizers from the resources

- Force deleting a PVC/PV

- A CSI driver failure that leaves the PV in a Failed state without deleting the cloud disk

The other storage trap is over-provisioned volume sizes. Developers request 100Gi “to be safe” for a database that holds 1Gi of data. Without a proper feedback loop, this could stay under the radar, and add up to your bill.

The Networking Layer: Where Convenience Defaults Become Expensive Habits

Networking costs in Kubernetes are the hardest to reason about and the easiest to accidentally inflate. The main offender is Service type LoadBalancer.

Every LoadBalancer Service provisions an actual cloud load balancer. Each one costs money just to exist, even before you account for data processing charges. In a cluster with dozens of microservices, it’s common to find teams exposing services externally that have no business being external, simply because LoadBalancer was the first Service type they learned.

The fix is well-known: use an Ingress controller (or the newer Gateway API) to consolidate external access behind a single load balancer and route by hostname or path. One load balancer instead of a dozen. But “well-known” doesn’t mean “consistently applied”. Without a policy preventing new LoadBalancer Services from being created, teams will keep doing what’s easiest.

Cross availability zones data transfer is the other networking cost that is often overlooked. Kubernetes schedules Pods across AZs for resilience, which is good. But when a Pod in eu-west-1a talks to a Pod in eu-west-1b, you pay inter-AZ transfer fees on both sides. For high-throughput services, this adds up fast. Some advanced features like topology-aware routing with topologySpreadConstraints and Service topology hints can help, but most teams don’t configure them because, again, nothing breaks without them.

Why Manual Audits Are Not Enough

You may think “we should plan a quarterly review to catch this”. This alone does not work. You may go through a detailed audit of your kubernetes cluster, identify wasted resources and try to delete orphaned volumes, disks, and Load Balancers, and right-size your workloads. You may also request other teams to right-size their workloads and properly manage their services, and hope they get time during their sprint to do so. The reality is that, next quarter you will run an audit and find the same problems.

A manual audit will definitely fall short in this case, because waste is a continuous problem.

Every kubectl apply can introduce new waste. Every deleted StatefulSet can leave behind orphaned storage. Every new Service can spin up an unnecessary load balancer.

The answer isn’t more discipline. It’s automation. Policies that prevent waste at admission time. Autoscalers that match capacity to actual demand. Dashboards that make cost visible before it becomes a crisis. This is what I think of as cost optimization as code: treating cost hygiene the same way we treat security and compliance: as something enforced by the platform, not left to human memory.